Part 1: The Idea

As tired, hard-working, and curious teachers participating in a weekend meeting for our Knowles Teaching Fellowship, the two of us sat on the floor of an office/yoga room in New Jersey. Having taught a full week and traveled across the country to meet with our Fellowship cohort to analyze and discuss data from our classrooms, our conversation strayed away from what it was supposed to be about. We think we were supposed to be discussing something about our inquiry data—we had asked a question and collected data to learn more about our classrooms. Instead of discussing our data or using the conversation protocol we were supposed to, we talked about how nerve-wracking it was to look critically at our teaching in this way. To be in a room of other highly accomplished teachers from around the country and share data about how a lesson really flopped or how status and social hierarchies affected our classrooms was scary and vulnerable.

We had been friends since the very beginning of our Fellowship, so three years into the five year program this was by no means our first time working together. Yet we still felt nervous about sharing about our teaching, classrooms, and students. Teaching can feel like an extension of ourselves, and being critical of our teaching feels like opening the door to being personally judged rather than professionally. Most teachers have likely experienced this: the sting from a lower-than-Exceeds-Expectations ranking on an evaluation or the anxiety you feel when inviting an outsider into your classroom. It seemed to both of us that we’d stumbled upon a pretty major roadblock to meaningfully engaging in inquiry, a foundational piece of the Fellowship. And it was one that no one had really talked about directly.

After finally saying this out loud, we laughed a bit about how both of us thought the other one was the better teacher, and it felt good to realize we weren’t alone in feeling nervous about sharing our teaching practice. It was freeing to let go of all the expectations we had for ourselves, and just be real people with each other instead of “perfect teacher” people. In that moment on the yoga room floor, we recognized that being vulnerable was foundational to sharing and learning from stories about our classrooms. Without that vulnerability, we couldn’t do the work we wanted to, which was to grow as teachers. We crept out of the yoga room and re-joined the rest of the meeting late with a new outlook and perspective about how to share ourselves and our teaching practice with others.

We have both reflected multiple times on this yoga room epiphany, which laid bits and pieces of the groundwork we’d do together for the rest of our time in the Fellowship. During the annual summer conference for our Fellowship, we both thought we could level-up our vulnerability practice and share our thinking about this with others. After many Zoom meetings, Google Docs, and feedback sessions, that is exactly what we did. Our presentation had the focus question: “How can understanding vulnerability, self-worth, and identity increase our ability to engage in and lead meaningful inquiry and collaboration?” Without understanding our own reactions to feeling vulnerable and being able to stay in a vulnerable space, we cannot successfully navigate personal inquiry or collaboration with other educators.

Part 2: The Stories

We centered our presentation around the idea of vulnerability, self-worth, and teacher identity in the classroom. We used Brené Brown’s work in her book Daring Greatly to ground our ideas. In particular, we used her definitions of vulnerability and self-worth and applied those ideas to teaching. She defines vulnerability as experiencing uncertainty, risk, or emotional exposure. When we began our presentation, we asked participants to share their associations with the word “vulnerability” and how they felt when someone provided feedback on their practice. We got responses like: “Defensive! They don’t know my class/students/context,” “Who are they to judge me?” and “I’m still learning—they haven’t seen me at my best” so we knew we weren’t alone in our experiences around vulnerability and feedback.

Figure 1

One-Word Participant Associations with the Word Vulnerability

Note. This figure was made with Poll Everywhere during our presentation.

Though our initial conversation about vulnerability had begun in the setting of sharing data from our classrooms, we quickly realized that vulnerability, self-worth, and teacher identity are hugely important aspects of not only being a teacher but also of collaboration and being a teacher-leader. In order to successfully navigate both individual inquiry and reflection or collaboration with other educators, we need to: (a) uncouple our self-worth from our success as teachers, (b) understand our own reactions to feeling vulnerable, and (c) learn to stay in a vulnerable space. For example, take this anecdote from Jamie’s first year of teaching:

As the other chemistry teacher very kindly shared all of her materials with me, she told me that first-year teachers have a higher failure rate than more experienced teachers. She meant to tell me this as reassurance, but I, of course, responded with a polite smile and the thought, “Challenge accepted.” I was petrified by the idea that my deficits as a first-year teacher would negatively impact my students. This fear made it nearly impossible to take feedback without feeling like I was failing. In order to protect myself, I unconsciously made the decision to avoid feedback as much as possible.

During our presentation, we shared this story to help illuminate the relationships between vulnerability, self-worth, and identity. According to Brown, self-worth is defined as our belief that we are all worthy of love and belonging. We feel vulnerable when our self-worth or identity is on display or up for debate. Though it would be far easier to just avoid vulnerability altogether, we cannot teach without infusing our identity into our teaching. The stories we tell, the activities we choose, even the classroom logistics we set up speak to our values as teachers and the meaningful learning experiences we had as students or learned from mentors as early-career teachers. We spend hours of time and buckets of energy trying to be good teachers and often hold ourselves to incredibly high standards.

When we base our self-worth on our students’ success, any critical feedback becomes personal and it damages our sense of worthiness.

But there is a difference between feeling vulnerable from being authentic in our classrooms and being vulnerable because our self-worth is on the line. In this particular scenario, Jamie had correlated her self-worth with her students’ academic performance, and it limited her ability to reflect and grow as a teacher. When we base our self-worth on our students’ success, any critical feedback becomes personal and it damages our sense of worthiness. This is different from engaging in feedback and reflection from a mindset of worthiness and growth. Receiving feedback will always be vulnerable! But by recognizing that our self-worth is not, in fact, based on our success as teachers, we can enter into that vulnerability and engage in the feedback and collaboration more easily.

After looking generally at the ideas of and relationships between vulnerability, self-worth, and identity, we then shared three stories of vulnerability with our participants and asked them to analyze the stories in a jigsaw style in breakout rooms. In the first round of the jigsaw, participants read the stories and were asked to consider how the teacher in each story reacted to feeling vulnerable in a collaborative setting. Participants then rotated into groups in which each participant had analyzed a different story. Jamie shared one of the stories, included below, for participants to analyze:

I grew up in a pretty small town with only one high school; this meant I had my mom for biology and for AP Biology! I loved this, and when I became a biology teacher I wanted to integrate as many meaningful experiences from her classroom as I could. I started with a Socratic seminar based on Aldo Leopold’s essay, “Thinking Like A Mountain.” My teaching team wanted to modify it to match the Socratic seminars the English department did and to spend less time on some of the supports Mom had used. I agreed to their modifications without a lot of pushback because I felt like they had more experience than I did. The lesson went ok with my honors students but didn’t seem particularly impactful, while my general students (who typically had lower reading levels) struggled. My colleagues weren’t surprised and stopped using it, but I was determined to make it work. I tried it for another year, with similar results. When I moved to Utah, I tried it one more time, thinking that my student population’s familiarity with hunting would help them connect to the story. Instead, students openly mocked the reading during the seminar. I was crushed by the negative responses and stopped using the essay in my classroom all together.

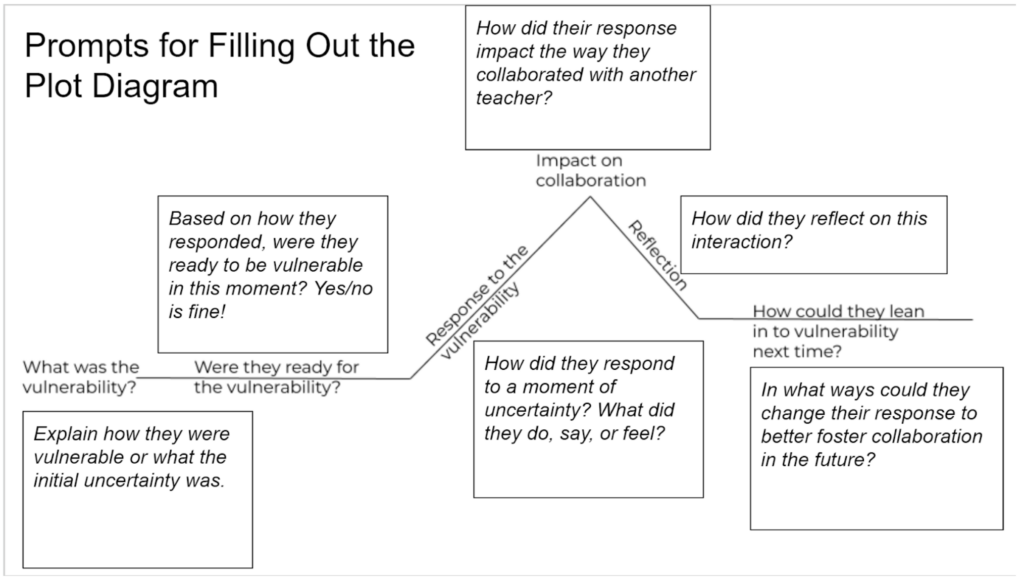

Our analysis tool was a plot diagram, likely familiar from your seventh-grade English class:

Figure 2

Analysis Template Participants Used During the Presentation

Note. This figure was created by Sara Abeita for the presentation.

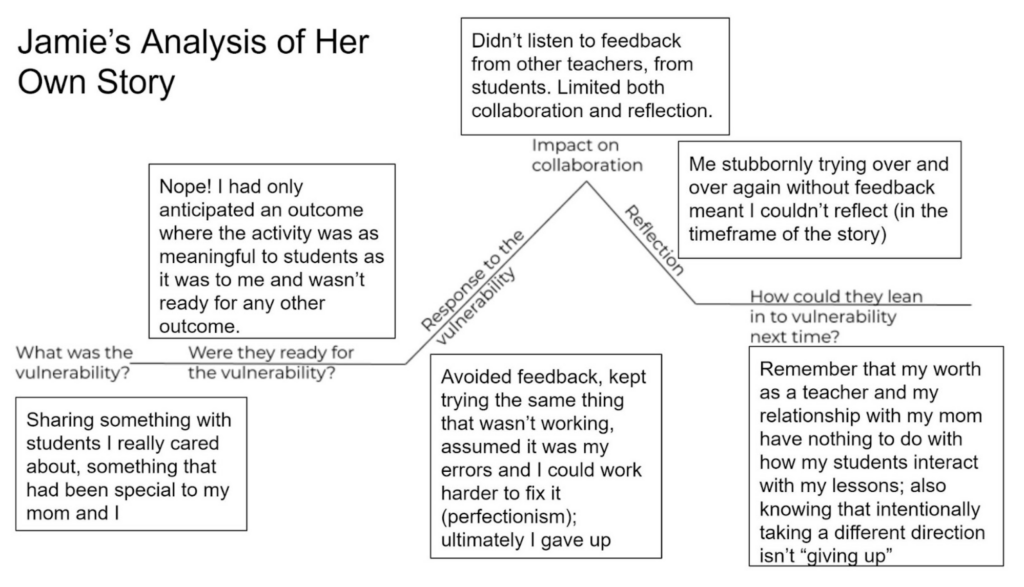

Jamie filled out the plot diagram for her own story, which you can see in Figure 3:

Figure 3

Jamie’s Filled Out Version of the Analysis Template

Because each participant had read a different story, they could look for patterns across the stories. As we listened in on their conversations, one main pattern emerged: when confronted with a vulnerable situation, the teachers in all three stories disengaged in some way. We stepped back and allowed the opportunity for more collaboration and/or leadership slip away.

Part 3: The Defense Mechanisms and Reflection Strategies

When we came back together as a whole group, we entered into a discussion about defense mechanisms that typically show up in response to vulnerability. Often we don’t realize we’re using defense mechanisms in the moment—we certainly didn’t while we were in the middle of living our stories! But until we can notice and become aware of our defense mechanisms, we remain locked out of the vulnerable moments that are necessary for reflection, collaboration, and leadership. Brown lists many defense mechanisms throughout her book Daring Greatly, but we focused on the ones that showed up for us in our stories.

In Jamie’s filled-out plot diagram, she mentioned “perfectionism” as one of her responses to struggling with her lesson. Perfectionism is the belief that we can avoid vulnerability if we just work hard enough and do everything perfectly. This defense mechanism also showed up in the other two stories, along with serpentining (the belief that we can avoid vulnerability if we are totally prepared before we begin something) and intellectualizing (avoiding vulnerability by generalizing and/or theorizing to move away from the emotions of the situation).

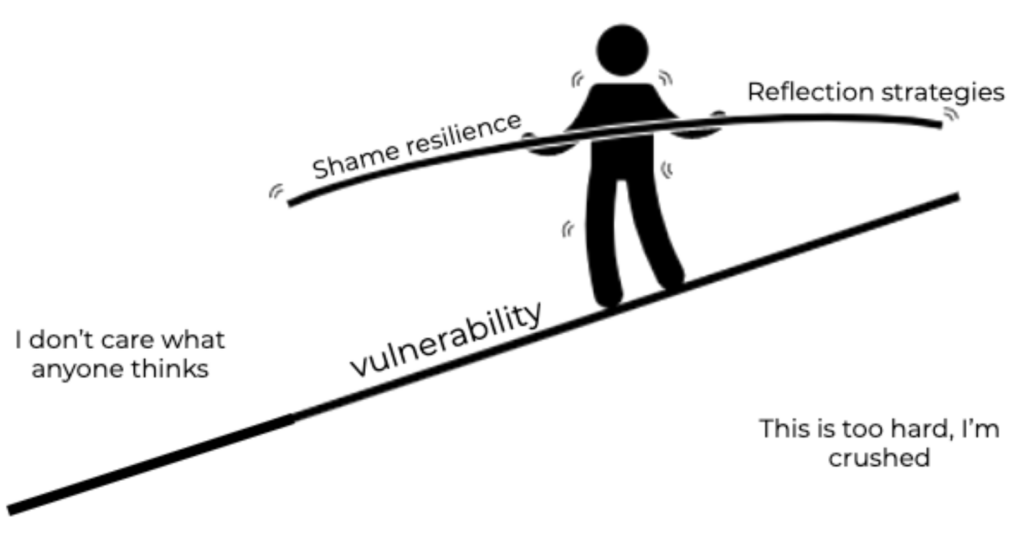

Everyone has some kind of defense mechanism, or more likely a cocktail of them, to help protect us from vulnerability. Though we mentioned three, there are lots more to explore. We know we identify with different defense mechanisms in different situations, and the more we’ve reflected on our own defense mechanisms the more we are able to notice and check them in order to stay in vulnerable situations, even though it’s really hard! Brown uses a tightrope as an analogy to help explain exactly what’s at stake in vulnerable situations:

Figure 4

Graphical Representation of the Tightrope Analogy

Note. This image was created by Sara Abeita for the presentation.

The idea behind this tightrope analogy is that in order to stay engaged with vulnerable moments (walk the tightrope), we must build up our shame resilience and practice reflection strategies (balance bar). Being vulnerable with other people can be scary, and it is easy to fall off on either side of the tightrope. On one side we fall into our fear of being judged, and are consumed by the moment, taking everything personally. Taking in feedback about ourselves is uncomfortable, and it can give way to endless thoughts of self-doubt and obsession. On the other side of the tightrope is the complete opposite—building a wall around ourselves and telling the story that we don’t care what others think. If you build the persona of not caring what others think, then you protect yourself from any kind of critique or possible shame. If we are going to walk this tightrope of vulnerability, we must toe the line between caring too much and caring too little about feedback we receive.

Because of both the difficulty and the importance of being able to stay “on the tightrope” (stay engaged in a vulnerable moment), we focused the rest of our presentation on the reflection strategies that act like a balance bar to help us be resilient in those vulnerable moments. This starts with becoming aware of our defense strategies and when we’re using them—often they’re so ingrained we don’t even notice. Sometimes noticing we’re using a defense strategy is the first moment we realize we’ve been in a vulnerable spot at all. Once we have this realization, we can respond more openly and thoughtfully.

If we are going to walk this tightrope of vulnerability, we must toe the line between caring too much and caring too little about feedback we receive.

For both of us, identifying our most common defense mechanisms allows us to take a deep breath, step back from the situation for a moment, and employ some reflection strategies that allow us to more clearly assess the vulnerable situation and make better choices about how we want to react.

To present other reflection strategies, we both shared an “update” to our story. Jamie’s update explained how she utilized a community of supportive peers, including Sara, to help her notice her defense mechanisms and realize when she is in a vulnerable situation. Jamie also identified the story she was telling herself about this particular lesson, which was about how failing at this lesson was somehow failing her mom. When she could discard that story, it became much easier for her to take feedback on the lesson and realize that the decision to change it out for something else that worked better for her students, in her context, was actually a good teaching move, not a failure.

We also included several other reflection strategies in our presentation to give our participants more opportunities to find something that resonated with them. The first was checking our assumptions about other people involved in the situation. For example, it’s easy to assume that a colleague doesn’t want to help students succeed because they demonstrate a deficit mindset, but it’s possible they just don’t have any practice using an assets-based or growth mindset. Another reflection strategy we talked about was seeking first to understand. By coming to a situation with an inquiry mindset or from a place of curiosity, we can take a step back from our own opinions and beliefs and defuse a lot of our own defensiveness. The last reflection strategy we shared was setting and communicating clear boundaries and expectations. These boundaries don’t remove vulnerability, but they do create safety that allows everyone to stay in a vulnerable space more easily.

By being aware of our defense mechanisms and using reflection strategies before, during, and after vulnerable moments, we can grow our ability to stay in vulnerable spaces. This allows us to be more authentic in our own classroom, and to collaborate and lead more effectively. But like all skills, this one can be complicated and takes a lot of practice!

Part 4: Reflections and Disclaimers

All of this work comes from the goal of trying to stay in vulnerable spaces longer and more productively to enable collaboration and leadership. However, this all comes with some major caveats. Being vulnerable is uncomfortable and we need to push ourselves to stay in vulnerable moments, but there are also times where situations move from being vulnerable to being unsafe. Being observed, receiving feedback on a lesson plan or pedagogy strategy, and sharing our teaching values are all potentially powerful moments, but those moments can also become unsafe, and it’s really important to recognize the difference. When critique shifts from our work to our identity or worth, when our experiences and knowledge are disregarded, or when people cross boundaries or break norms, these are unsafe situations. It is especially important to consider situations in which we or our colleagues are in unbalanced positions of power or privilege, because it becomes even easier for vulnerable situations to become unsafe. When faced with them, we do not need to continue pressing ourselves forward in the name of vulnerability; in fact, this is why boundaries are such an important part of being able to be vulnerable in the first place.

Despite the potential pitfalls of navigating vulnerable moments, we know (and our participants agreed) that we can’t expect to grow as teachers or teacher leaders without figuring out how to enter these spaces. Being vulnerable helps to build trust within our communities, which can be a powerful agent for much needed changes in our educational settings. Through building trusting and strong relationships, we open ourselves up to being more than just one person but a community of people working, growing, and enjoying our profession. It is scary to open up or invite vulnerability into our practice, but we have both found that in most cases, the reward outweighs the risk.

At the end of all of this, as we reflected together on vulnerability, we wanted to acknowledge that it is still hard. After our presentation in the summer of 2020, we didn’t even look back at the feedback we asked participants to give us on our presentation for several months. After all the hard work, Google Docs, and hours on Zoom, it felt scary to see what people thought about our presentation, which was about embracing vulnerability and feedback—ironic, right? Vulnerability, trust, and growth are difficult. Even in established relationships like ours, it can be easier to avoid the vulnerability than to open ourselves up to it. But without the vulnerability that came from looking at our feedback, we couldn’t grow from the experience of giving our presentation. Embracing that you can’t be perfect at anything, including vulnerability, is a big part of being a leader. After finally looking at our feedback, we noticed that our participants were overwhelmingly thankful for the vulnerability that we modeled, and were excited to build their balance bars of shame resilience by identifying defense mechanisms and practicing reflection strategies.

Embracing that you can’t be perfect at anything, including vulnerability, is a big part of being a leader.

In many cases, being vulnerable means that you have to give up some control, that sometimes as teachers we are used to having. It requires more listening than speaking, which can be difficult, especially when your own work is being critiqued. That being said, vulnerability is empowering. We are still constantly revising our own understanding of vulnerability and how it fits into our practice, but it is clear to us that growth occurs when we engage in vulnerability rather than run away from it. That growth helps us identify our own strengths and weaknesses, all while building community and trust with those around us.

From our summer presentation, we realized that our participants wanted to continue the conversation we began, and turn the focus on themselves. We provided our own stories to lower the risk for our participation, but after modeling that, they still wanted more. They wanted to enter that space with us, which really illustrated the power of vulnerable collaboration and leadership. We are hopeful that after reading this, you too will feel empowered to embrace the vulnerable moments you experience and identify ways to leverage them into leadership.

Sara Abeita, a Knowles Senior Fellow, currently teaches various levels of biology at Free State High School in Lawrence, Kansas. Sara was awarded the Outstanding Biology Teacher Award by the Kansas Association of Biology Teachers in 2020. She enjoys biking, hiking, reading, and spending time with her husband and dog. Reach Sara via email at sara.abeita@knowlesteachers.org and on Twitter at @AbeitaBiology.

Jamie Melton, a Knowles Senior Fellow, taught primarily biology during her six-year career, along with human anatomy and physiology, chemistry, Earth science, geology, and seventh-grade science. Jamie is an HHMI BioInteractive ambassador and loves presenting to share resources with other teachers. Currently, Jamie lives in Ogden, Utah, and is taking a year off to stay home with her first child. Reach Jamie via email at jamie.melton@knowlesteachers.org.