Building Thinking Classrooms: A Conversation on Implementation

As you read this article, you probably fall into one of three categories; either you’re deep in the process of your own Building Thinking Classrooms (BTC) implementation adventure, you have enough background to be curious about what all the fuss is about, or maybe you haven’t heard about BTC at all.

This interview examines the practices laid out in Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics by Peter Liljedahl (2021), through the lens of two teachers—one early-career and one veteran. These teachers will share their successes with the practices as well as how they’ve adapted, addressed challenges, and which practices they skip altogether. Through the experiences of these two teachers, we’ll gain a deeper understanding of what it takes to turn theory into practice and elevate the power of reflection while implementing any new framework or curriculum regardless of the content you teach.

My own BTC journey began a few years ago while with a group of early-career math and science teachers at the Knowles Annual Conference. The hotel conference room in downtown Philadelphia was abuzz with phrases like, publicly randomized groups, lesson consolidation, stop thinking questions, and vertical non-permanent surfaces. I was even chastised as a facilitator for asking participants to write their thinking on a large piece of paper placed on the flat table in front of them: “Are you aware that the risk of making mistakes is lowered when you don’t have to write your thinking on paper?” Needless to say, I was intrigued; what exactly constitutes a Thinking Classroom? Who is this Liljedahl guy? And in what universe would I ever refer to a whiteboard as a “vertical non-permanent surface?”

[I] found my whole understanding of what math teaching and learning could look like had shifted.

So, I picked up a copy of Building Thinking Classrooms, read it cover to cover, and found my whole understanding of what math teaching and learning could look like had shifted.

The basic premise of the book, and Liljedahl’s 15 years of research, is that there are entrenched institutional norms that we enact in schools every day which are actually counterproductive to students being able to think deeply. These institutional norms include everything from the way the furniture is arranged to the notebooks students write in.

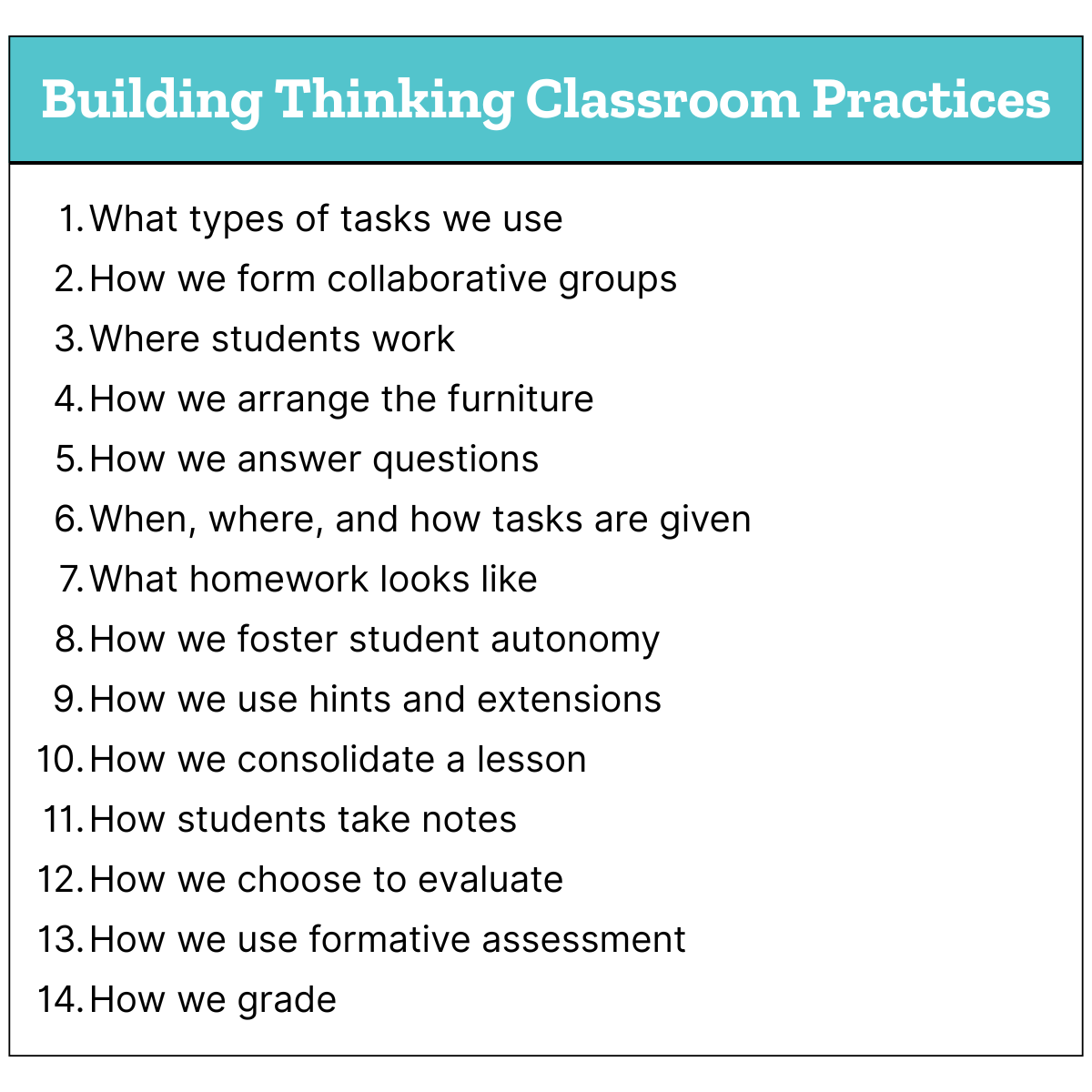

As Liljedahl describes in the book, his quest was to answer: what happens when you intentionally break institutional norms? Does student thinking increase? Can we learn to make moves that give students no choice but to think? From this research emerged 14 factors that Liljedahl claims are the variables that can most improve the likelihood of students thinking (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Teaching practices to modify in improving thinking in classrooms (Liljedahl, 2021, p. 14)

But what does it actually look like or feel like to be in a thinking classroom? Fast forward a few years later to another hotel conference room overlooking a suspiciously lush golf course in Phoenix, AZ. A tall, charismatic Swede, with strawberry blonde hair, glasses, and a patterned shirt strides confidently to the back of the space as participants whisper, “there he is!” Over the next several hours, Peter Liljedahl himself demonstrated to a room full of teachers how to bring these practices to life.

“All right everyone, stand up, come gather back here. Closer! Closer! That’s it, get closer! Can you all see? Look at this! Isn’t this interesting? What do you notice? What do you wonder?” (practice 1) Liljedahl introduced a math task on a small whiteboard (practice 4), gave us the next step we needed to work on (practice 6), passed out the deck of playing cards that told us which small group to go to (practice 2), and we were off to the races solving the task together at a standing whiteboard (practice 3). Each time we finished a problem we were handed increasingly more complex challenges (practice 9). The one time Liljedahl stopped by my group’s board, his only comment was some variation on, “Is that always true?” or “Can you find something else that would work?” (practice 5). Eventually we all took a walk with our fellow participants to talk through the strategies we used and think about patterns that emerged in our work. This allowed us to do two things. First, we consolidated our learning (practice 10)—considering patterns that emerged in our work helped us solidify our understanding of the mathematics. And second, talking to others encouraged what Liljedahl calls knowledge mobility—a circulation of ideas and understandings among all participants. Next, we explored a tech tool, Magma Math, that BTC has teamed up with (perhaps because they are a Swedish company, but definitely because they are developing interesting formative assessments—and the Swedish gummies at the tables didn’t hurt either).

Ok, this all sounds amazing. Students thinking deeply about math, a classroom without a “front of the room” and knowledge just flowing from student to student. Why isn’t everyone doing this immediately? Perhaps it’s because the framework laid out in the BTC book is just that, a framework. How it lives and dies in the classroom is based on how actual teachers, teaching actual students all over the country, interpret the words and modify the practices to fit the needs of their contexts. Thus, the impetus for this interview. Two teachers—in different states, with different levels of experience, teaching students of different age groups, both deep in their own learning—open the doors of their classrooms for us to learn from them in order to better serve our own students.

First we have my mother-in-law, Laura, who has over two decades of teaching experience, is a 2014 Presidential Award for Excellence in Math and Science Teaching recipient, and someone who I’ve been talking about teaching with for the entirety of my career. As a preservice teacher, I flew from my home in Colorado to observe her 6th grade math and science classroom in Burlington, VT. I was completely enamored with the cacophony of joyous noise in her classroom and her ability to pose interesting questions to students, who then had to grapple with them together. No taking notes off the overhead projector in that classroom, even way back then in the late aughts. Laura jumped on the BTC train early—her whole team has collaborated around creating assessments with BTC in mind. Her answers to my questions reflect her years of experience in the classroom and her inclination to innovate coupled with her critical approach to new resources.

I met the second respondent, Clare, almost 5 years ago. She is a 2022 Knowles Teacher Initiative Fellow and a 4th year high school math teacher in Michigan. Clare, through her funding from Knowles, attended a BTC conference the summer following her first year of teaching, and the rest is history. She now regularly writes and presents about her journey. Clare’s reflections on implementing BTC in her classroom highlight the importance of having a community of practitioners to come along with you—critical friends who will continue to push your practice as a teacher each and every year.

The following responses by Laura and Clare have been edited for clarity.

Question 1: When did you first hear about BTC and what appealed to you?

Laura: I learned about BTC by reading Robert Kaplinsky’s blog post. Robert is a math instructor and thinker who I really admire and he thought it was one of the most profound things he had ever read regarding math instruction, so I bought the book. I loved the idea of group thinking and problem solving and I am always looking for ways to do math instruction better.

Clare: I first heard of BTC during the winter of 2021. I was just finishing a super amazing student teaching experience in a physics classroom where we used a modeling curriculum and I was determined to find something similar in a math classroom because that is what I wanted to teach with my first job. I spoke with my former education professor and asked him several questions relating to how to find the perfect school with the perfect curriculum that would align with my teaching philosophy. He told me this perfect school most likely didn’t exist, but he introduced me to the book Building Thinking Classrooms and my vision of a math classroom changed forever.

Question 2: What went well for you in your first iterations?

Laura: I had a treasure trove of “non-curricular tasks” because I have been a devotee of Jo Boaler and her Week of Inspirational Math for years. I felt like starting off the school year that way was something I was super comfortable with. BTC gave me permission to try big thinking tasks for more than one week, which I loved. I liked having a structure for group work. The idea of publicly randomizing grouping suddenly made so much sense, and I have always loved vertical whiteboards.

Students were truly comfortable working with everyone, they knew each other's names, they supported each other, and they were more than willing to share and explain their ideas to the whole class.

Clare: I started utilizing BTC practices at the end of my first year of teaching when I utilized a grant to purchase materials, such as whiteboards and my iPad. During this initial iteration, I focused on the BTC practices of random grouping, types of tasks, and where students work. The first thing I noticed after implementing these practices was how much more engaged my students were with each other. Previously, when students sat in groups I hoped they would talk to each other, but rarely would I see every group actually talking about the task. Having this shared vertical whiteboard space made it easier for students to collaborate and increased student white board talk tremendously.

During my second year of teaching, I utilized many of the BTC practices from day one. My biggest observation from starting at the beginning of the school year was the community it developed in my classroom. Students were truly comfortable working with everyone, they knew each other’s names, they supported each other, and they were more than willing to share and explain their ideas to the whole class. I truly think the BTC practices allowed my students to feel confident and brave as learners in my classroom.

Question 3: What was challenging in your first iterations?

Laura: I have the utmost respect for teachers who are able to devise systems where all students are doing their part at the boards. My motivated mathematicians begged for the thin slicing (designing tasks to continuously increase in complexity) to get more and more challenging, whereas my less motivated mathematicians spent a lot of time trying to hide from doing the thinking. I have found having all students participate very challenging.

The biggest change for me is that I will no longer answer stop thinking questions—questions that signal that students want me to do the thinking instead of them. That was so hard to train myself out of, it drives them crazy but has really made them think more independently. I have a love-hate relationship with giving instructions as soon as the scholars arrive and sending them directly to the boards. I know that according to research, students have the most energy for sustained attention at the beginning of class. However, I have yet to feel like I have found a way to consolidate a lesson successfully while the scholars are standing. Instead, for the last few years, I have started my classes with “What do you notice? What do you wonder?” type problems. I am loath to give up those fascinating conversations we have had that make math real and often visual.

I sometimes think the author has not taken into consideration those students with lower social or academic status in the classroom or the ones with individualized education plans (IEPs) who really need some very explicit instruction. I have watched them just get run over at the boards, with other students leaving them out of the conversation entirely. The only thing our 6th grade team has used that addresses this is to tell the scholars we will be making a circuit around the room. When we get to your group each of you will pick a cube. The one with the star has to explain the “why” of the math. We had to resort to a point-based system because otherwise they ignored the scholar they are not excited to work with. However, if everyone has to be prepared to explain the why, great conversation happens.

Clare: The biggest challenge I faced with BTC practices was still getting students to shift their understanding that they have agency as learners. No matter how much I talked about knowledge mobility among students and told them I didn’t need to approve every step of their thinking process, they still always wanted to go to me first when they had a question about their work or how to start their process. Although there is a whole chapter dedicated to “How We Answer Questions,” it was difficult for my students to understand that I wasn’t going to give them feedback for every step of their process. Based on my student feedback survey, there was a shift in their understanding that I wasn’t the only one they could learn from, but that didn’t change their behavior of who they asked for help.

Another challenge I faced was how I consolidated each task. In the book, Liljedahl talks about using gallery walks and other discussion methods for students to talk about their work to consolidate a task. Gallery walks are useful when there are divergent tasks, however many of the algebra 1 tasks I gave were convergent and it often felt repetitive when I had students explain their board or another board to the class.

Question 4: In what ways have you collaborated with others on this work and what has been beneficial about that experience?

Laura: We have a highly functioning sixth grade professional learning community and we work together to plan the thin slicing of concepts and problems, create mild, medium, and spicy independent work to differentiate complexity, create our notes sheets, and design assessments that are also mild, medium, and spicy and allow all students to take the same test without modification, but also challenge themselves. It would be a lot to take on by yourself without a team to work together to create everything. I love watching other teachers. I would also love to spend time in a classroom where a teacher was doing this well and see what it looks like.

The constant collaboration with my colleagues and friends allows me to continually reflect on how the BTC practices are impacting my students…

Clare: Last year, I opened my classroom for all of my colleagues to come watch me teach with BTC practices. This interested a lot of people due to the high level of student engagement they noticed. After this, I had a few teachers in my department start using BTC practices in their classroom and my department chair bought books for everyone so I could lead a book study. This book study was helpful because it gave us time to discuss and reflect on the BTC practices and how to tweak them to allow for more learning to occur in the classroom.

Additionally, I have a friend, Josh, who teaches at a neighboring district and uses BTC practices in his Algebra 1 classes. We meet up once a month to discuss what is working and what needs more support. Plus, we both visited each other’s classrooms for a day to provide feedback on what we noticed. This summer, Josh and I presented at the BTC conference to share our successes with combining BTC practices and restorative practices to create positive classroom communities. The constant collaboration with my colleagues and friends allows me to continually reflect on how the BTC practices are impacting my students and how I can improve my practices to better support my students.

Question 5: What are you definitely not going to use this year?

Laura: I am not going to consolidate learning while the students are standing. It has not been successful. I have learned that thinking is hard and tiring and most students would prefer not to have to do it, but that when they do think something through themselves the level of pride is unmatched. I have learned that I need to be really flexible about what a successful class looks like. I wish I could ask the author: What have you seen to be successful for those who are disengaged? How do you help students who are learning English? How would you partner with special educators to make sure students’ IEP goals are being worked on and met?

Clare: After going to the 2nd Annual BTC Conference in the summer, I am not going to be using a digital platform for random grouping. Liljedahl talked about how this, especially at the secondary level, can cause lots of bullying. Using playing cards to do the sorting goes against the ideal situation of the random groups happening all at once. To combat one of the issues I had with a regular deck of cards (students were trading cards as I was in the hall), I made a custom set of cards with four different symbols so students are not aware of the random grouping I will do until I start class.

Question 6: What are you still tweaking?

Laura: Everything. We still tweak everything. All the time. There are some elements of BTC that I do with fidelity. I always publicly randomize groups. We always have three at a board and the pen moves every two minutes. I have found a way to make BTC’s strategy that encourages students to capture their thinking in “Notes to My Future Forgetful Self” into deep thinking notes that the scholars work on and share with others. Those have been my successes.

I have found that I cannot send them to the boards every day. They lose interest and motivation. On days they go to the boards, doing independent thin-sliced tasks, I try to get them started right away, but no more than two or three times a week. My most successful consolidations have been when I don’t attempt to consolidate in the BTC way. I am much more successful and I can see students’ learning when I hold a traditional mathematician’s meeting—where we sit in a respectful circle and discover together what we are learning. I use talk moves to have the students lead the conversation about what they have discovered. I will sometimes take photos of the work and pop it on the smartboard for students to explain or discover. Having them lead the conversation, agree, disagree, and explain to each other has been my most effective methods.

Clare: The beauty of BTC practices is that they are always changing. At the 2nd Annual BTC Conference this summer, Lijedahl talked about how he still doesn’t know the answers to everything and has changed up his practices since writing the book. With that being said, I am constantly reflecting on the BTC practices, talking about the BTC practices with critical friends, and making tweaks every day!

After reading the responses from both teachers, a few potentially instructive commonalities emerge.

First, the power of our colleagues. Both Clare and Laura were introduced to BTC by trusted sources. Finding your people, those who inspire you and push your practice, is essential for adopting new practices. Second, they both found success with randomized grouping, and vertical whiteboards, noting that student discourse and collaboration increased, as well as feeling as though they could try more complex rigorous tasks more often.

Something both teachers struggled with was breaking students’ reliance on the teacher. While Laura trained herself to ignore stop thinking questions, Clare leaned into the idea of knowledge mobility, where students can and should be “cheating” off of each other, looking at how other groups are attempting to solve the problem. Another common difficulty was the practice of consolidation. Laura has been playing around with where consolidation happens physically and Clare is thinking about how to reduce repetition.

I imagine Laura and Clare will have made significant changes since they originally responded to the questions! For example Laura would really like to think more about how to address the needs of English language learners, those with IEPs, and truly disengaged students. Clare is working on refining how she handles random groups, and how she can support student agency so that consolidation can go more smoothly. Both teachers show us that they view this framework as dynamic and continually evolving.

What are you left thinking about in your own practice after reading the reflections of these two exemplary teachers? Could the practices of BTC help make student thinking more visible in your classroom?

Citation

Fretz, M. (2026). Building thinking classrooms: A conversation on implementation. Kaleidoscope: Educator Voices and Perspectives, 12(2), https://knowlesteachers.org/resource/building-thinking-classrooms-a-conversation-on-implementation.